Antiamphibious barriers of the Atlantic rampart "Rommel's asparagus". Gates and gates for panel fences Belgian gates

The city gate Kruispoort on the Langestraat is one of four surviving gates in the city of Bruges. In the first half of the 9th century, the De Burg fortress was surrounded by defensive walls with four gates. The city grew and in 1127-1128 the city was surrounded by a new fortress wall with seven city gates. However, all these structures have not survived to the present day.

The third belt of the fortress walls with 10 city gates was built in 1297. A deep ditch was dug in front of the walls. Four fortress gates have been preserved to this day. The Kruispoort gate (porte Sainte-Croix) on Langestraat street from the outside consists of two massive round towers with many loopholes, built in 1402, to protect the approaches to the city from the northeast. An earthen rampart stretching from the north marks the location of the city wall.

A drawbridge over the Ringvaart canal leads to a vaulted wide passage inside the fortress wall. The passage can be blocked in case of danger with massive wooden gates. Nearby is a small pedestrian passage, it can be reached through the second bridge. On the inside, at the corners of the structure, there are two octagonal towers.

Nearby are the Lace Museum, the Jerusalem Church, the Folklore Museum, the Museum of the Flemish poet Guido Gezelle and other attractions.

Description

Press release

One of the recent trends is craft beer. It can now be found even in "non-beer" establishments. The most delicious craft is Belgian. In Belgium, in a small area (only 12 times the size of modern Moscow), thousands of types of beer are produced.

There are more and more Belgian pubs in Moscow. There are still not as many as in St. Petersburg, but there are already plenty to choose from, not just from the “Cell” in Sivtsevo.

Principled position: not a single drop of beer bottled locally.

The taste of beer depends primarily on local water. That is why the bottled Hugaarden, which is poured at the San-Inbev Klin plant, is not very tasty to drink. At '0.33' it comes from Belgium and it's a completely different drink: subtle, refreshing, fragrant, smelling of oranges and coriander.

The second principle is a serious emphasis on bottled beer. The tradition of preferring draft beer to bottled beer (they are supposedly tastier and fresher) does not work in the case of Belgian beer. A significant part of the “beers” undergoes secondary fermentation (i.e. fermentation) in the bottle. At ‘0.33’ you can compare the bottled and draft version - and see how much stronger and richer the taste is in the bottle.

Bottles of 400+ brands. This is the best collection in Russia. One fruit beer, which the fair sex loves so much, more than fifty (!) Pieces. Beer sommeliers are open on Thu, Fri and Sat. Tastings are held regularly.

To make the beer uncompromisingly fresh, only a few varieties were put into bottling at '0.33' (one of the most popular in each category): Gordon Five Belgian Lager, Palm Amber Ale, Leffe Light and Dark Monastery Ale, White Blanche de Bruxelles, Light Cherry Lambic Mort Subite, exquisite dark Bourgogne des Flanders, strong fruity PetrusAged Red, incredible abbey double Floreffe Prima Melior and one of the most legendary Belgian brands - Pauwel Kwak .

Another tap is the beer of the month.

And last but not least, prices. The best among all Moscow Belgian brasseries. We at ‘0.33’ are following this ourselves and asking everyone to help us.

Chef ‘0.33’, Sergey Sergeevsky, has developed a small but decent menu. Inspired by Belgian beer specialties, talentedly adapting them to local tastes. Hits: our version of the Belgian burger on a potato waffle, fillet american (tartar in our opinion), homemade sausages and pâtés, real waterzoi (peasant chicken or fish stew), the perfect Nicoise (the way they make it in Nice) , a plate of sizzling juicy meatballs with a crispy crust, croquettes, chicken wings in chutney sauce, perfect Belgian french fries (Belgium is the birthplace of this dish), stewed beef cheeks, which are called “stoffles” in Belgium, steaks of flawless roasting. When fresh mussels are brought from the Crimea, they are served in white wine, in beer, in cheese or tomato sauce. Well, Liege waffles with ice cream.

On weekdays until 16:00 a huge (33%) discount on food.

A few words about the interior: huge panoramic windows through which it is pleasant (not without a sense of secret superiority) to observe the eternal traffic jam in Orlikovo, a diverse space, many cozy nooks, lamps hanging over the tables create a comfortable twilight. Brick, wood and rough metal contrast with soft leather sofas.

There is a banquet hall for approx. 30 people, a huge screen for sports broadcasts, and five bathrooms (to avoid queues).

And finally, ‘0.33’ has its own Manneken Pis, the famous Brussels Manneken Pis.

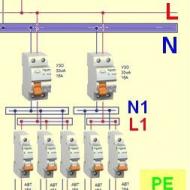

- The design is made in the factory

- Written warranty of 10 years on appearance and 50 years on mechanical properties

- No need to repaint or touch up welds annually

- The kit includes stainless steel fittings manufactured by Locinox (Belgium)

- A special Locinox lock is used for all-weather outdoor performance with a long working resource

- Locinox hinges are adjustable in three directions (solution to problems with seasonal adjustment)

The main element of gates and wickets is fittings that ensure the normal functionality of the entrance group for a long time under different weather conditions.

Gates and gates of panel fences Grand Line Profi, Medium, Bastion, Protect are supplied with fittings Locinox (Belgium). Locinox hinges, locks, crossbars are made of stainless steel, certified and designed specifically for outdoor all-weather use. This is confirmed by special tests that all Locinox products pass. During the tests, the fittings withstand 150,000 opening/closing cycles, which indicates a large working resource, and only after that the locks leave the factory for the facility.

Gates and gates of panel fences are made of galvanized steel bar GOST 3282 and a frame made of galvanized steel. Before painting, wickets and gates go through 9 stages of preparation, including the application of the OXSILAN conversion layer. This ensures that the gates and wickets will retain their original appearance for 10 years.

Mounted product samples can be viewed at the factory in Vorsino at the fence exhibition.

Gates and gates Profi, Bastion, Protect

| Gates | |

| Width, m - 3.00 - 9.00 (step 0.5 m) | |

| Opening angle 180°. Opening inward and outward perimeter. | |

| Kit includes: 2 poles, Locinox GBMU4DSHIELD hinges, Locinox LAKQ U2 lock, keys, 2 bolts Locinox VSF |

|

Gate |

| Filling - panel Profi, Bastion, Protect | |

| Height, m - 1.53; 1.73; 2.03; 2.43 | |

| Width, m - 1.00 | |

| Opening angle 180°. Opening inward and outward perimeter, left. | |

| Location of hinges and locks: Hinges on the left, lock on the right (type A) - to be specified when ordering |

|

| Kit includes: 2 posts, Locinox GBMU4DSHIELD hinges, Locinox LAKQ U2 lock, Locinox SAKL QF slat, keys |

| Hinges Locinox GBMU4DSHIELD | Lock Locinox LAKQ U2 | Gate leaf retainer Locinox UGC | Latch for crossbars Locinox OGS |

|

|

|

|

| Adjustable from 20 to 50 mm, opening angle 180° | Lock with handle and slat | It is concreted to the desired height and keeps the leaves of the gate or gates open | It is concreted at the junction of two swing gate leaves and fixes the gate leaves in the closed state |

Locinox produces a wide range of interchangeable fittings, so you can choose a complete set of gates and gates specifically for your needs and requirements.

Gates and gates Medium

|

Gates |

| Filling - Medium panel (without stiffeners) |

|

| Width, m - 3.50; 4.00; 4.50; 5.00; 6.00 | |

| Opening angle 100°. Opening inward and outward perimeter. | |

| The kit includes: 2 posts, Locinox GAM12 hinges, Locinox LTKZ lock, slat, keys, deadbolt |

|

Gate |

| Filling - Medium panel (without stiffeners) | |

| Height, m - 1.03; 1.53; 1.73; 2.03 | |

| Width, m - 1.00 | |

| Opening angle 100°. Opening inward and outward perimeter, left. | |

| Location of hinges and locks: Hinges on the right, lock on the left (type B) - standard equipment |

|

| Set includes: 2 posts, Locinox GAM12 hinges, Locinox LTKZ lock, slat, keys |

In 1939-1940, in the east and north-east of Belgium, a system was formed of several defensive lines of different depths, echeloned from the eastern border to Brussels. The Dil line in this system was the second of the rear lines that covered Brussels from the east, and, unlike the others, was completely completed by construction. The river and canal formed a natural anti-tank barrier for most of the position. On the section from Antwerp to Leuven, 194 long-term structures with machine gun weapons were located in three lanes, from Leuven to Wavre - 21 structures in one lane and 20 more - to the west of Wavre. Further to Namur, there were two lines of anti-tank barriers made of railway rails dug into the ground, metal tetrahedrons and C-elements (“Belgian gates”), however, due to lack of funding, not a single firing structure was built on this site. In total, more than 400 bunkers were built, and the line itself crossed Belgium from Koningshooikt to Waver and had a length of about 70 km. Hence the name KW-line. Thus, the Diehl line adjoined its northern end to the fortress of Antwerp - part of the so-called National Redoubt, and its southern end to the fortified area of Namur.

The backbone of the HF line consisted of one or two rows of combat bunkers. Where possible, they were integrated into canals, railways and flooded areas. For example, hundreds of hectares of land were flooded along the Diel at Haate, Sint Joris Werth, Sint Agatha Rode and Florival. In such areas, one row of bunkers was enough for a solid defense. In cases where no existing or natural obstacles could be used, a second line of combat bunkers was built as an additional reinforcement. Important places, such as villages and major crossroads, were protected by additional combat bunkers, the so-called anti-tank centers. Combat bunkers were at a distance of several hundred meters from each other. In front of the bunkers, rows of numerous obstacles were equipped: anti-tank barriers (Cointet elements, rails dug into the ground and tetrahedra) and anti-tank ditches. The idea in the construction of numerous bunkers was to fire from them to destroy the enemy who had stopped in front of obstacles.

Although not immediately apparent, the HF line consisted of a wide variety of bunkers, mostly seven types. Almost every combat bunker had its own design, which adapted it to a specific location. As a result, there are no two completely identical combat bunkers on the entire defensive line. At the same time, some structural elements were common to each bunker. So, loopholes for machine guns, viewing slots, air intake holes were the same everywhere. Typical were external and internal armored doors and emergency exit hatches, other structural details.

The bunkers themselves, of a rather primitive design, were built of reinforced concrete with walls up to 1.3 m thick, which could withstand a shot of 150-mm guns. The armor of the outer doors was 3 mm, internal - 5 mm, and was recruited from metal strips fixed at an angle, which provided additional protection against armor-piercing bullets. The size of the bunker for one shooting place was 2mx2m and a height of 1.85 m. The ceiling was sheathed with galvanized steel corrugated plates to protect the crew from fragments if a projectile hit the bunker. The emergency exit had a size of 0.6m x 0.6m and was laid with two rows of metal beams, which were removed only from inside the bunker. All bunkers had several special air ducts, which, in addition to supplying air, also allowed the grenade to be rolled out if the bunker was surrounded by the enemy. Moreover, they had a large slope, which did not allow anything (a grenade or explosives) to be thrown inside the bunker. There was no water supply, no electricity, no sanitary facilities in the bunkers. Lighting was provided by oil or kerosene lamps.

The bunkers were disguised as the environment. Some of them were painted in camouflage colors or covered with camouflage nets, for which iron hooks were mounted on the roof of the bunkers. Others had false windows and doors. Sometimes a false wooden house, barn, stable, or other structure adapted to the specific area was built around the bunker. Bunkers built on the slopes of hills, banks of rivers or reservoirs were masked by an earthen embankment, leaving loopholes and a manhole in the roof open.

Each shooting place in the bunker had a rectangular hole in the wall with a viewing slot. Both the embrasure and the viewing slot could be closed with an armored shutter from the inside. A number (1,2 or 3) was applied with white paint over each shooting place. The numbering was introduced to facilitate the management and work of the calculation in the bunker. To install machine guns, in front of the embrasures there was a mount for a rack or a machine gun.

The calculation of the bunker depended on the number of machine guns intended to be installed in it - from one to three. In most cases, the bunkers had to be armed with two Maxim machine guns. The calculation of the bunker consisted of eight people: the commander of the calculation, two sergeants, two ammunition carriers and two gunners.

Along the Leuven-Diel canal, special small bunkers for one shooter were created, although their value from a military point of view is very doubtful. Such bunkers did not have an emergency exit.

It should be noted that the weapons in the bunkers were not installed in advance, but had to be installed by those units that were ordered to occupy the defense line, using their standard weapons.

Behind the line of bunkers, a few kilometers away, an underground telephone network was built, which was supposed to provide communication at the front and with the front. To ensure stable communication, in case of breaks and accidents, it had two parallel telephone cables at a considerable distance from each other and interconnected by cross lines. In places of cross connections, bunkers (telephone wells) were built on the surface of the earth, outwardly similar to combat bunkers, but much smaller and without loopholes and emergency exits. In these wells, field lines from bunkers were also connected to the general network. In fact, they were a kind of telephone exchange. Sometimes they were called command bunkers (chambre de connection), because from them it was possible to monitor the actions at the front and control the course of the battle. Each such bunker was served by one signal soldier. Typically, the size of such a bunker was 1.3m x 0.7m. A total of 33 such bunkers were built.

The basis of the protection of the HF line between the constructed bunkers was various artificial and natural barriers that impede the passage of both military equipment, including both tanks and infantry. One of these barriers was the "Cointet" (C-element) or "Belgian gate" elements.

The "Cointet" element was developed by the French General Edmond de Coentet de Filhain (1870-1948) based on the idea of Russian anti-cavalry fences used in the First World War. It was made of metal corners bent from a sheet, had a three-dimensional triangular shape. The front panel of the "Cointet" element had a width of 2.9 m and a height of 2.4 m. For installation, the element had a base - a metal tail about 3.3 m long. All structures - about 1300 kg. The sections were fastened together with metal loops. Often, the fastening was replaced or reinforced with a steel cable stretched inside the structures and fixed to concrete "anchors".

Such "walls" served primarily as a serious obstacle for the infantry during the attack, forcing the infantryman to climb over the "wall", thereby "substituting" for the machine-gun fire of the bunkers. These barriers were also an obstacle for armored vehicles, armored personnel carriers and even light tanks (up to 20 tons), especially those connected with thick steel cables. It cannot be said that they were insurmountable for them, but the delay in pulling them apart was enough for the artillery to concentrate and knock out an almost immobilized tank. To eliminate such obstacles with artillery fire, a fairly accurate and massive shelling was needed, since almost a direct hit was required to break the wall. Neither fragments nor explosive warfare harmed her. And most importantly, after the attack, the defending infantry restored the “wall” in a matter of hours, replacing the damaged sections and restoring their connections to each other. For medium and heavy tanks, such obstacles were like toys, but at that time there were no such tanks in Germany.

As conceived by the creators of Cointet, this design could also be used simultaneously as a basis for creating barricades, for which the space behind the lattice was filled with soil, stones and other objects.

About 75 thousand sections of "Cointet" were produced by order of the Belgian army by several civilian factories. On May 10, 1940, 73.6 thousand pieces or more than 200 km were installed on the line. They were installed in fields, roads, near bridges and tunnels, at crossings and crossroads, as well as in other places where there were no natural obstacles. After the occupation of Belgium, almost all the elements of Cointet were dismantled by the Germans and reassembled on the Atlantic Wall.

Today, the original of the “Cointet” element can only be found in a museum, but the “anchors” for attaching them are a very common artifact along the fields and roads of Belgium.

The second popular obstacle on the HF line was the so-called "railway fields", which covered the tank-dangerous directions. They were pieces of railway rails buried in rows (from five to eight rows) to a depth of two meters. Above the ground, the rail protruded to a height of about a meter, and the space between them was densely braided with barbed wire. Sometimes such fields were supplemented with an anti-tank ditch.

Tetrahedra were used as anti-tank barriers, which were metal trihedral pyramids with a face height of 2-2.5 m. Two types of tetrahedra are known: light ones weighing up to 200 kg, and heavy ones filled with concrete inside and weighing up to 500 kg. They lined up in three to five rows, and in fact were impassable for any equipment without engineering barriers.

The most serious anti-tank barriers were systems of anti-tank ditches with one or two concrete walls, which, through the use of dams on rivers, were filled with water. Thus, an anti-tank wall 3.6 km long with a channel 4 m wide was erected in Haat.

Several cities behind the HF line, as well as road junctions or strategic heights, were protected by anti-tank centers, which were several bunkers around the protected object, in the middle of which anti-tank guns were installed. There were about a dozen such centers along the line.

Thus, the defensive line created by Belgium, in the opinion of the Belgian military, was supposed to hold the country's defenses from the north, in the event of a breakthrough of the first line. The French and British military command considered the Belgian defense weak, and the Belgian army unable to prevent the Germans in an effort to quickly capture Belgium and the Netherlands. Therefore, in order to shorten the front line in advance, move it away from the vital centers of France and bring its air bases closer to the Ruhr region, it was supposed to take up defense on fortified lines on Belgian and Dutch territory. In Belgium, the Diehl line was such a frontier. It was supposed to saturate the defensive line with the troops of Belgium, Britain and France, in pre-distributed areas. However, prior to the start of the German invasion of Belgium, no French or British officer had been on the Diehl line and were not familiar with the terrain and fortifications. As a result, the allies, having occupied their sites on the line, could not hold the defense on the Dil line for more than one or two days.

By the time of the German invasion of Belgium, the HF line consisted of an underground telephone network, machine-gun bunkers, anti-tank obstacles, flooded areas and water-filled ditches. However, there were almost no trenches and trenches for infantry, there were no minefields, and there was no barbed wire. The retreating troops and the French and British approaching from the rear were supposed to bring weapons and ammunition with them.

On May 15, 1940, when fighting was still going on near individual forts of the first defensive line of Liege, the advanced units of the Germans had already reached the line of the Diel line. On May 16, the French leave the line of defense, since the Germans have already partially entered France, and the garrison from Belgium leaves, fearing encirclement. On May 22, the British leave. May 28 Belgium capitulates. During the 18 days of the war, the Belgian army lost 6 thousand people, or half of the regular strength. Approximately the same number of civilians were killed. The defensive line turned out to be an absolutely useless undertaking.

Many remnants of this line are still visible in the Belgian landscape today. Most of the bunkers were never destroyed - neither by the Germans during the war, nor by the Belgians after. Most of them remained abandoned, some were adapted by the local population for household needs, some captured colonies of flying mice.

Other remains of the line have also survived: separate sections of anti-tank ditches, both filled with water and dry. There are also some gateways. However, both of them are in an abandoned, unattractive state. Often there are concrete "anchors" from the "Iron Wall". So far, not a single museum has been created along the entire length of the line, and materials on the defense of the line in open sources are very scarce.

Living in a world that has not known major wars for two-thirds of a century, it is not at all easy to imagine the scale and intensity of the great battles of World War II. The success of the Anglo-American-Canadian troops on D-Day - June 6, 1944 - is a well-known fact that has entered the history books. But can we imagine what those who stormed the French coast, bristling with death, experienced and endured from the sea? After all, the enemy, already rapidly losing strength, was still insidious and dangerous.

The construction of the Atlantic Wall is in full swing. Behind the inclined logs, a series of obstacles in the form of tetrahedrons can be seen.

Armory of the Atlantic Wall The beaches of the northern coast of France were equipped with rows of different types of barriers, designed to perform the same task - to prevent landing craft from approaching close to the coast.

A fragment of a topographic map of the Omaha sector. Red color shows the lines of obstacles that the Allied landing force had to overcome

Tank tower on a concrete base. Normandy Coast, Omaha Sector

After the tragic end of the “strange war” for the anti-Hitler coalition and the evacuation of the British from Dunkirk, Hitler planned to build on his success and land an amphibious assault on the British coast in order to finish off the most dangerous enemy in Western Europe. However, in the summer of 1941, the Seelówe (“Sea Lion”) operation was decided to be postponed until the end of the “blitzkrieg” against the USSR. The Germans, obviously, hoped that then the British would become more accommodating and agree to the conclusion of a peace favorable to Germany. But the failures on the Eastern Front made it completely forgotten about the invasion of England - and vice versa, the threat of an allied landing on the coast of France became more and more real. By Directive No. 40 of March 23, 1942, Hitler ordered the start of work on the creation of the Atlantic Wall, which was to be a system of fortified areas similar to the Maginot Line.

Beach War

However, until the summer of 1943, this wave existed to a greater extent on the pages of newspapers. The length of the coastline of the Atlantic coast of France, where landing is theoretically possible, is more than 1400 km. It is simply unrealistic to create a continuous defensive line of such a length. It is possible to cover only the most likely directions.

By this time, on all fronts, the strategic situation had changed not in favor of Germany. In May, the Italo-German troops in North Africa capitulated. Sicily fell in July. In July-August, the defeat in the Battle of Kursk finally deprived the Wehrmacht of a strategic initiative. The Allies then landed in Italy and advanced northward. However, it got bogged down in difficult terrain and did not promise prospects.

By this time it became clear to both Hitler and the allies that a landing operation on the coast of France was inevitable.

In November 1943, Hitler instructed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had gained vast experience in operations in North Africa on terrain poor in natural obstacles, to inspect the Atlantic Wall and accelerate measures to build a line of defense on the coast.

Rommel took into account that the balance of power for the Wehrmacht would be extremely unfavorable and there was no other choice but to try to compensate for it through a system of barriers on the coast - in those places where a landing was most likely. This was supposed to be done primarily by erecting barriers that could prevent small landing craft from approaching the water's edge for landing infantry and unloading heavy weapons.

The field marshal also took into account the fact that the height of the tide in the English Channel can reach 15 m, and in the best case for the allies - at least 6-7 m. This meant that at the time of full low tide, the water leaves the coast by 150-400 m When landing at low tide, paratroopers find themselves on absolutely flat terrain without the slightest shelter.

Rommel believed that the Allies would attempt to land at the time of high tide: this would eliminate the need to overcome the deadly hundreds of meters. But if you create a line of barriers with a height of about 3 m, approximately from the water's edge at low tide to the water's edge at high tide, then this option is excluded. Barriers will prevent boats from approaching the shore at high tide. They will have to land at low tide, and this creates favorable conditions for the destruction of the paratroopers. The next echelon and boats with ammunition for the first paratroopers will have to wait for the next low tide, which will come only after 12 hours. This time will be enough for the Germans to destroy the landed and prepare for further events.

However, there was no point in laying anti-tank and anti-personnel mines on the bottom - the boats would simply float above them. Ordinary non-explosive barriers are also ineffective due to their low height.

Of course, the Germans took into account that the paratroopers could overcome the beach zone, and therefore, by the end of 1943, on the coast, where the tide did not reach, more than 2 million mines alone were laid.

However, Rommel believed that the allied soldiers should not be allowed to cling to the shore. They must be destroyed when they are still helpless, that is, they are on board the landing craft.

Cogs, sticks and gates

The problem was that the mines, which would later be called anti-amphibious, simply did not exist at that time. German specialists in the field of barriers had to improvise. A number of ideas were put forward by the "Desert Fox" himself - Field Marshal Rommel. It was he who thought of combining the properties of non-explosive barriers with anti-tank mines.

The first (closest to the water) barrier belt was to be located along a line of two meters depths in the middle of the high tide, the second belt - at a depth of 4 m at the time of full low tide, the third and fourth - between the first and second belts. However, due to the difficulties of working in the water and the lack of the required number of divers, the first barrier belt had to be created on the line of the lowest water level at low tide.

The first belt consisted of log barriers, which the Germans called Hemmbalken, and inclined logs dug into the ground. An anti-tank mine was fixed at the top of each barrier. The height of both is about 3 m.

By themselves, inclined logs posed a serious danger to landing barges and boats. If a moving boat ran into a log, it pierced the bottom and got stuck inside. The floating craft lost its course and became an easy target for cannons and machine guns. The paratroopers could not leave the ship, because the depth here was too great. Well, the explosion of a mine attached to a log made a hole, and the ship sank.

Hembalks (Hemmbalken) had two or three metal plates with teeth on the upper surface of the log, which ripped open the bottom of the craft and did not allow it to work out the reverse. When the ship moved at a good speed and crawled onto an inclined log, this led to its capsizing, if it had not previously hit a mine fixed at the top point. According to Army Group B (Heeresgruppe B) ledgers, 517,000 such barriers were installed along the English Channel coast. Anti-tank mines were placed on 31,000 of them.

The gaps between the groups of hembaloks were to be closed by "Belgian gates" (Belgian gates) - mobile metal barriers that really resembled gates.

To a greater extent, all these obstacles were intended for the infantry, but the watercraft could not overcome them either.

The Nutcracker without Tchaikovsky

The next row of barriers was, according to some sources, personally invented by Field Marshal Rommel, according to others, anti-amphibious mines developed according to his idea, called NuІknackemine, that is, “nutcracker mines”. Obviously, the Germans imagined that these mines would split enemy ships like nutcrackers.

Perhaps Rommel's anti-amphibious mines can be considered the first bottom-type anti-amphibious mines.

In the first version, the "nutcrackers" were massive concrete cone-shaped bases weighing 600–700 kg, inside which one or two anti-tank mines or an explosive charge weighing 10–12 kg were placed. A rail or an I-beam 3 m long protruded obliquely from the base. It played the role of a lever target sensor, and when the landing barge ran into this beam, the mines exploded, and the hydro-shock wave tore the engine, shafts and rudders from the mounts. The hull received numerous cracks through which water entered. It was impossible to close them up, especially since the crew and paratroopers received shell shock during the explosion and they themselves needed help. And since the depth of the water in this place was more than 3 m, there was little chance of survival.

The first "nutcrackers" were distinguished by their cunning. The fact is that when installing such mines, the Germans did not put explosive charges in them. British scouts, who repeatedly landed at night at the beginning of 1944, reported that these were ordinary non-explosive anti-amphibious obstacles. The charges were inserted only in the last days before the Allied invasion. How many British and American sappers on D-Day this mistake cost their lives remains unknown.

However, as cement became more and more scarce (it was not enough even for pillboxes), concrete rings, which are used to line the walls of wells and culverts, and stocks of captured large-caliber French shells, went into action. The standard fuses were unscrewed from the shells and the fuses of the pressure (D.Z.35) or tension (Z.Z.35) action, which were usually used in improvised anti-personnel mines, were inserted.

Ultimately, concrete was abandoned altogether, and in the last months before the Allied invasion, a new version of the Nutcracker was installed on the beaches. These mines were simply a frame of I-beams, on which an artillery shell with a tension or pressure fuse was attached with clamps. Such a mine was powered by the same inclined steel beam.

It soon became clear that the "nutcracker mines" very quickly covered with sand and silt, and only the beam remained visible. It seemed that the sea itself undertook to help the Wehrmacht. After all, it could never have occurred to anyone that the pieces of rails sticking out of the sand were part of an explosive device, and not a simple barrier.

From Moscow to Normandy

Behind the line of anti-landing mines was a line of concrete tetrahedrons with sections of rails or steel beams built into their tops. Their height was already less than three meters, since the maximum water level at high tide was kept here for a short time.

Even further from the water, in one or more rows, ordinary anti-tank gouges and anti-tank hedgehogs were put up, partly carefully assembled and taken away by the Germans back in 1941 from near Moscow, partly made and improved by diligent Czech workers at factories in Brno, Ostrava and Prague. These barriers were already intended for tanks that were lucky to survive at the water's edge. According to the testimony of the American General Omar Bradley, in the Omaha landing site, out of 33 tanks that landed in the first wave of landings, 27 drowned and died on anti-amphibious obstacles.

In case the Allies did start their landings at high tide and chose a day when the tide was at its highest and all of the above devices were too deep, the last line of barriers was made up of three-meter-high curved steel structures.

However, these barriers were arranged rather for intimidation - their main task was to force the skippers to refuse to approach the shore. These structures were very clearly visible at any time of the day from the air and from the sea, and it was they who were originally given the nickname "Rommel's asparagus." Then this name spread to all antiamphibious barriers. In the post-war period, “Rommel’s asparagus” for some reason also began to be called barriers invented by Rommel against the landing of gliders, and at the same time paratroopers (high thin poles interconnected on top with barbed wire).

The Germans, in setting up barriers, at first proceeded from the fact that the Allies would begin landing by the time of the highest tide, in order to slip over the shoal that was exposed at low tide and be as close as possible to the main coast. Therefore, until the middle of 1943, the main attention was paid to the installation of wire obstacles and anti-personnel mines where the tide no longer reaches.

Field Marshal Rommel, who arrived at the Atlantic Wall, came to the conclusion that the Allies could time the landing to a full ebb, and ordered the installation of anti-amphibious barriers and mines on the shallows, that is, in the tidal zone.

However, the development of the barrier system was hampered by April storms. Many structures were covered with sand, demolished and destroyed by waves, some of the mines either exploded or failed. Much had to be hastily restored. Not everything was successful.

Blood Sector "Omaha"

As is known from history, the paratroopers who stormed the French coast had the hardest time in the sector code-named "Omaha". Here, in the zone of responsibility of the American troops, "Rommel's asparagus" proved to be the most effective way.

For the Allies, a successful landing in the Omaha and Utah sectors was very important, since success made it possible to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula in the future, and then capture the deep-water port of Cherbourg there in order to supply troops from England. The significance of the peninsula was well understood by the Germans. Therefore, anti-amphibious barriers were developed here to a greater extent than in other places.

However, the barriers themselves could not stop the landing paratroopers. They could only complicate their actions and create favorable conditions for the defenders to destroy the enemy. On the Omaha sector, the Americans were not lucky: the Germans transferred to the peninsula, to help the very weak 709th Infantry Stationary Division, which was located here, the 352nd Infantry Division, formed from the remnants of the 321st Infantry Division destroyed on the Eastern Front, whose commanders learned to fight in heavy battles with the Red Army. Thus, the Omaha sector was actually defended by two infantry regiments.

At 5:50 am on D-Day, support ships began a massive bombardment of German positions on the coast. Time "H" (the time when the bow of the first landing craft should touch the shore) was scheduled for 6:30, that is, an hour after the start of high tide. This made it possible to land the first assault groups (eight infantry battalions) and sappers (14 underwater demolition teams) as close as possible to the first row of barriers. After that, the sappers had only 30 minutes to make passes, since during this time the water rises by 60 cm and further work on the barriers becomes impossible.

The landing of the main forces of the first wave of landing was planned for 7:00. Five minutes before that, Sherman tanks, equipped with equipment to allow them to swim, and tank landing barges with the rest of the tanks were supposed to rush into the aisles. They were entrusted with the task of providing fire support to the infantry before it would be possible to land the artillery on the beach. However, the circumstances were unfavorable for the tankers. The sappers came under heavy German fire, and most of them were destroyed. Only five passages were made, however, they were not properly marked. In addition, a storm arose in the strait, and as a result, the tank-landing barges did not get into the aisles. Of the 32 tanks, only five were landed on the shore. Time played against the landing. The tide hid the barriers and passages in them under the water.

So, on the western flank at Dog Grim, Alpha Company of the 116th Regimental Group was to land from six infantry landing barges. The first barge hit the barrier and sank along with the paratroopers. Then the same fate befell two more barges. Three barges still managed to reach the water's edge, but the infantrymen fell on the shallows under machine-gun fire and returned to the water in the hope of hiding behind their broken barges. Rising water drove them to the German machine guns, and the wounded simply drowned. Company losses reached 66%, and as a combat unit it ceased to exist.

By the time the second wave landed at 7:00 am, the barriers began to hide under water, and the passages in them were not so marked.

By 08:00, not a single unit was able to overcome the coastal shallows. Those who were lucky enough not to get stuck at the water's edge found themselves pressed against the precipitous bank by fire and suffered losses, and it was impossible to land reinforcements and heavy weapons due to obstacles and dense fire. The landing at the Omaha sector was thwarted. At 08:30, the site commander ordered the suspension of further landings. At that time, 50 tank landing barges unsuccessfully searched for passages in the barriers, but only the LCT-30 barge managed to reach the shore and only by 10:30 in the morning, that is, with a big delay from the schedule.

By noon, General Bradley ordered the barges to be diverted to the Utah sector and into the British landing zone at the Juno sector, where there were few barriers. In addition, only one battalion of the 709th Infantry Division held the defense in the Utah sector. The landing there was more or less successful.

The success of D-Day was predetermined by the fact that the Germans did not have the opportunity to create a sufficiently powerful system of barriers along the entire front of the Allied landings. And most importantly, by the summer of 1944, the Eastern Front had so bled the Wehrmacht that there was simply no one to fight on the Normandy coast.

A huge role was also played by the significant superiority of the allied aviation and navy over the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine. Nevertheless, the experience of Omaha, sad for the allies, confirmed that a developed, well-thought-out and echeloned system of anti-amphibious obstacles to a large extent equalizes the chances of a weaker enemy with a stronger one.