What are the main reasons for the Crusades? Causes of the Crusades (briefly)

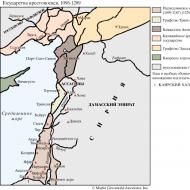

Crusades (late 11th – late 13th centuries). Campaigns of Western European knights to Palestine with the aim of liberating the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem from Muslim rule.

First Crusade

1095 - at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban III called for a crusade to liberate holy places from the yoke of the Saracens (Arabs and Seljuk Turks). The first crusade consisted of peasants and poor townspeople led by the preacher Peter of Amiens. 1096 - they arrived in Constantinople and, without waiting for the knightly army to approach, crossed over to Asia Minor. There, the poorly armed and even worse trained militia of Peter of Amiens was defeated by the Turks without much difficulty.

1097, spring - detachments of crusading knights concentrated in the capital of Byzantium. The main role in the First Crusade was played by the feudal lords of France: Count Raymond of Toulouse, Count Robert of Flanders, son of the Norman Duke William (the future conqueror of England) Robert, Bishop Adhemar.

Also taking part in the campaign were Count Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine, his brothers Baldwin and Eustathius, Count Hugo of Vermandois, son of the French king Henry I, and Count Bohemond of Tarentum. Pope Urban wrote to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos that 300,000 crusaders were going on the campaign, but it is more likely that several tens of thousands of people took part in the First Crusade, of which only a few thousand knights were well armed.

A detachment of the Byzantine army and the remnants of the militia of Peter of Amiens joined the crusaders.

The main problem of the crusaders was the lack of a unified command. The dukes and counts who took part in the campaign did not have a common overlord and did not want to obey each other, considering themselves no less noble and powerful than their colleagues.

Godfrey of Bouillon was the first to cross over to the land of Asia Minor, followed by other knights. 1097, June - the crusaders took the fortress of Nicaea and moved to Cilicia. The Crusader army marched in two columns. The right was commanded by Godfrey of Bouillon, the left by Bohemond of Tarentum. Godfrey's army advanced along the Dorylea valley, and Bohemond advanced through the Gargon valley. On June 29, the Nicaean Sultan Soliman attacked the left column of the crusaders, which had not yet managed to move away from Dorilea. The Crusaders were able to build a Wagenburg (closed line of convoys). In addition, their location was covered by the Bafus River. Bohemond sent Godfrey a messenger with a detachment to notify him of the approach of the Turks.

The Turks rained down stones and arrows on Bohemond's infantry, and then began to retreat. When the crusaders rushed after the retreating, they were unexpectedly attacked by Turkish cavalry. The knights were scattered. Then the Turks broke into Wagenburg and slaughtered a significant part of the infantry. Bohemond managed to push back the enemy with the help of a cavalry reserve, but reinforcements approached the Turks, and they again pushed the crusaders back to Wagenburg.

Bohemond sent another messenger to Godfrey, whose column was already hurrying to the battlefield. She arrived in time to force the Turks to retreat. Afterwards, the crusaders reformed for the decisive attack. On the left flank stood the South Italian Normans of Bohemond, in the center were the French of Count Raymond of Toulouse, and on the right were the Lorraineers of Godfrey himself. The infantry and a detachment of knights under the overall command of Bishop Adhemar remained in reserve.

The Turks were defeated, and their camp went to the winner. But the light Turkish cavalry was able to escape pursuit without much loss. The heavily armed knights had no chance of keeping up with her.

The Turks did not undertake new attacks on the combined forces of the crusaders. However, crossing the waterless rocky desert was an ordeal in itself. Most of the horses died from lack of food. When the Crusaders eventually entered Cilicia, they were greeted as liberators by the local Armenian population. The first crusader state was founded there - the County of Edessa.

1097, October - Godfrey's army captured Antioch after a seven-month siege. The Sultan of Mosul tried to recapture the city, but suffered a heavy defeat. Bohemond founded another crusader state - the Principality of Antioch.

1098, autumn - the army of the crusaders advanced towards Jerusalem. Along the way, she captured Accra and in June 1099 approached the holy city, which was defended by Egyptian troops. Almost the entire Genoese fleet, carrying siege weapons, was destroyed by the Egyptians. But one ship was able to break through to Laodicea. The siege engines he delivered enabled the crusaders to destroy the walls of Jerusalem.

1099, July 15 - the crusaders took Jerusalem by storm. On August 12, a large Egyptian army landed near Jerusalem, in Ascalon, but the crusaders managed to defeat it. Godfrey of Bouillon stood at the head of the Kingdom of Jerusalem they founded.

The success of the First Crusade was facilitated by the fact that the united army of Western European knights was opposed by disparate and warring Seljuk sultanates. The most powerful Muslim state in the Mediterranean - the Egyptian Sultanate - only with great delay moved the main forces of its army and navy to Palestine, which the crusaders managed to defeat piece by piece. This reflected a clear underestimation by the Muslim rulers of the danger threatening them.

For the defense of the Christian states formed in Palestine, spiritual knightly orders were created, whose members settled in the conquered lands after the bulk of the participants in the First Crusade returned to Europe. 1119 - the Knights of the Temple were founded, the Order of the Hospitallers, or Johannites, appeared somewhat later, and at the end of the 12th century it appeared.

Second Crusade (briefly)

The Second Crusade, which was undertaken in 1147–1149, ended in vain. According to some estimates, up to 70,000 people took part in it. The Crusaders were led by King Louis VII of France and German Emperor Conrad III. 1147, October - German knights were defeated at Dorileus by the cavalry of the Iconian Sultan. Afterwards, epidemics hit Conrad's army. The emperor was forced to join the army of the king of France, with whom he had previously been at enmity. Most German soldiers chose to return to their homeland. The French were defeated at Khonami in January 1148.

In July, the crusaders besieged heavily fortified Damascus for five days to no avail. 1149 - Conrad and then Louis returned to Europe, realizing the impossibility of expanding the borders of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Third Crusade (briefly)

In the second half of the 12th century, Saladin (Salah ad-Din), a talented commander, became the sultan of Egypt, which opposed the crusaders. He defeated the crusaders at Lake Tiberias and captured Jerusalem in 1187. In response, the Third Crusade was proclaimed, led by Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, King Philip II Augustus of France and the English king.

While crossing one of the rivers in Asia Minor, Frederick drowned, and his army, having lost its leader, disintegrated and returned to Europe. The French and British, moving by sea, captured Sicily and then landed in Palestine, but were generally unsuccessful. True, after a siege of many months, they took the fortress of Accra, and the king of England captured the island of Cyprus, which had recently separated from Byzantium, where he took rich booty. The Lusignan kingdom arose there, becoming a stronghold of the Crusaders in the East for a century. But strife between the English and French feudal lords caused the king of France to leave Palestine.

Deprived of the help of the French knights, Richard was never able to take Jerusalem. 1192, September 2 - Richard signed a peace with Saladin, according to which only the coastal strip from Tire to Jaffa remained under the control of the crusaders, while Jaffa and Ascalon were previously destroyed by the Muslims to the ground.

Fourth Crusade (briefly)

The Fourth Crusade began in 1202 and ended in 1204 with the conquest of Constantinople and a significant part of the possessions of Christian Byzantium instead of Palestine. The capital of the empire was stormed on April 13, 1204 and plundered. The first attack, which was launched on the 9th from the sea, was repulsed by the Byzantines.

Three days later, with the help of swing bridges, the knights climbed the walls. Some of the crusaders entered the city through a gap made with the help of battering guns, and already opened three Constantinople gates from the inside. Inside the city, the crusader army no longer encountered any resistance, since few defenders fled on the night of April 12-13, and the population was not going to take up arms, considering the fight pointless.

After the Fourth Campaign, the scale of the following crusades was significantly reduced. 1204 - King Amaury Lusignan of Jerusalem tried to assert his power in Egypt, stricken by drought and famine. The Crusaders defeated the Egyptian fleet and landed at Damietta in the Nile Delta. Sultan al-Adil Abu Bakr concluded a peace treaty with the crusaders, ceding to them Jaffa, previously conquered by the Egyptians, as well as Ramla, Lydda and half of Saida. After which, for a decade there were no major military conflicts between the Egyptians and the Crusaders.

Fifth Crusade (briefly)

The Fifth Crusade was organized in 1217–1221 to conquer Egypt. It was led by the Hungarian King Andras II and Duke Leopold of Austria. The crusaders of Syria greeted the newcomers from Europe without much enthusiasm. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, which had experienced a drought, found it difficult to feed tens of thousands of new soldiers, and it wanted to trade with Egypt rather than fight. Andras and Leopold raided Damascus, Nablus and Beisan, besieged, but never captured the strongest Muslim fortress of Tabor. After this failure, Andras returned to his homeland in January 1218.

The Hungarians were replaced by Dutch knights and German infantry in Palestine in 1218. It was decided to conquer the Egyptian fortress of Damietta in the Nile Delta. It was located on an island, surrounded by three rows of walls and protected by a powerful tower, from which a bridge and thick iron chains stretched to the fortress, blocking access to Damietta from the river. The siege began on May 27, 1218. Using their ships as floating battering guns and using long assault ladders, the crusaders took possession of the tower.

Having learned about this, the Egyptian Sultan al-Adil, who was in Damascus, could not bear the news and died. His son al-Kamil offered the crusaders to lift the siege of Damietta in exchange for the return of Jerusalem and other territories of the Kingdom of Jerusalem within the borders of 1187, but the knights, under the influence of the papal legate Pelagius, refused, although the Sultan promised to find and return even pieces of the True Cross captured by Saladin.

Pelagius actually led the army, reconciled the different groups of crusaders and brought the siege to an end. On the night of November 4-5, 1219, Damietta was stormed and plundered. By that time, the vast majority of its population had died of hunger and disease. Of the 80,000, only 3,000 survived. But the crusaders rejected Pelagius’s offer to go to Cairo, realizing that they did not have enough strength to conquer Egypt.

The situation changed when, in 1221, new detachments of knights from southern Germany arrived in Damietta. At the insistence of Pelagius, al-Kamil's peace proposals were again rejected, and the crusaders attacked the Muslim positions at Mansura, south of Damietta. His brothers from Syria came to the aid of al-Kamil, so that the Muslim army was not inferior in number to the crusaders. In mid-July, the Nile began to flood, and the crusaders’ camp was flooded, while the Muslims had prepared in advance for the rampant elements and were not harmed, and then cut off the path of retreat for Pelagius’s army.

The crusaders asked for peace. At this time, the Egyptian Sultan was most afraid of the Mongols, who had already appeared in Iraq, and chose not to tempt his luck in the fight against the knights. Under the terms of the truce, the crusaders left Damietta and sailed to Europe.

Sixth Crusade (briefly)

He led the Sixth Crusade in 1228–1229. German Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. Before the start of the campaign, the emperor himself was excommunicated by Pope Gregory IX, who called him not a crusader, but a pirate who was going to “steal the kingdom in the Holy Land.” Frederick was married to the daughter of the King of Jerusalem and was about to become ruler of Jerusalem. The ban on the campaign did not in any way affect the crusaders, who followed the emperor in the hope of booty.

1228, summer - Frederick landed in Syria. There he was able to persuade al-Kamil, who was at war with his Syrian emirs, to return Jerusalem and other territories of the kingdom to him in exchange for help against his enemies - both Muslims and Christians. The corresponding agreement was concluded in Jaffa in February 1229. On March 18, the crusaders entered Jerusalem without a fight.

Then the emperor returned to Italy, defeated the pope's army sent against him and forced Gregory, under the terms of the Peace of Saint-Germain of 1230, to lift his excommunication and recognize the agreement with the Sultan. Jerusalem, thus, passed to the crusaders only due to the threat that their army created to al-Kamil, and even thanks to the diplomatic skill of Frederick.

Seventh Crusade

The Seventh Crusade took place in the fall of 1239. Frederick II refused to provide the territory of the Kingdom of Jerusalem for the crusader army led by Duke Richard of Cornwall. The Crusaders landed in Syria and, at the insistence of the Templars, entered into an alliance with the emir of Damascus to fight the Sultan of Egypt, but together with the Syrians they were defeated in November 1239 in the Battle of Ascalon. Thus, the seventh campaign ended in vain.

Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade took place in 1248–1254. His goal again was the reconquest of Jerusalem, captured in September 1244 by Sultan al-Salih Eyyub Najm ad-Din, who was helped by 10 thousand Khorezmian cavalry. Almost the entire Christian population of the city was slaughtered. This time, the leading role in the crusade was played by the King of France, Louis IX, and the total number of crusaders was determined at 15–25 thousand people, of which 3 thousand were knights.

At the beginning of June 1249, the crusaders landed in Egypt and captured Damietta. At the beginning of February 1250, the Mansura fortress fell. But there the crusaders themselves were besieged by the army of Sultan Muazzam Turan Shah. The Egyptians sank the Crusader fleet. Louis' army, suffering from hunger, left Mansura, but few reached Damietta. Most were destroyed or captured. The king of France was among the prisoners.

Epidemics of malaria, dysentery and scurvy spread among the captives, and few of them survived. Louis was released from captivity in May 1250 for a huge ransom of 800,000 bezants, or 200,000 livres. At the same time, the king was demanded that the crusaders leave Damietta. The remnants of “Christ’s army” went to Accra. Soon, in the same 1250, Turan Shah was killed, and the Mamluks, hired soldiers in the service of the Sultan, came to power. Muiz Aybek became the first Mamluk sultan. Under him, active hostilities against the crusaders practically ceased. Louis remained in Palestine for another 4 years, but without receiving reinforcements from Europe, he returned to France in April 1254.

Ninth Crusade

The ninth and last crusade took place in 1270. It was caused by the successes of the Mamluk Sultan Baybars. The Egyptians defeated the Mongol troops in the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. 1265 - Baybars captured the crusader fortresses of Caesarea and Arsuf, and in 1268 - Jaffa and Antioch. The crusade was again led by Louis IX the Saint, and only French knights took part in it. This time the target of the crusaders was Tunisia.

The size of the Crusader army did not exceed 10,000 people. By that time, the knights no longer sought far to the East, as they easily found work in Europe, constantly shaken by feudal strife. The proximity of the Tunisian coast to Sardinia, where the crusaders gathered, and Louis’s desire to have a base for attacking Egypt from land played a role. He hoped that Tunisia would be easy to capture, since there were no large forces of Egyptian troops there.

The landing in July 1270 was successful, but soon a plague epidemic broke out among the crusaders, from which Louis himself died on August 25. His brother Charles I, King of the Two Sicilies, arrived in Tunisia with fresh forces, thereby saving the crusader army from collapse. On November 1, he signed an agreement under which the Tunisian emir resumed the full payment of tribute to the kingdom of the Two Sicilies. After this, the crusaders left Tunisia. After the failure of the Ninth Campaign, the days of the crusaders in Palestine were numbered.

1285 - Mamluk Sultan Kilawun of Egypt captured the fortresses of Marabou, Laodicea and Tripoli in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Accra remained the last stronghold of Christians in Syria. 1289 - a truce was concluded between Kilawun and King Henry II of Cyprus and Jerusalem, but it was soon broken by Henry’s troops, who invaded the border areas of the Mamluk state. In response, the Sultan declared war on the crusaders.

The Accra garrison, reinforced from Europe, numbered 20,000 men. But there was no unity in the ranks of Christians. In the fall of 1290, Kilawun set out on a campaign, but soon fell ill and died. The army was led by his son Almelik Azsharaf. In March 1291, the Muslims approached the walls of Accra. They had 92 siege engines. Truce negotiations proposed by the city's defenders were unsuccessful. On May 5, the Sultan's army began the assault. The day before, King Henry arrived in Accra with a small army, but on the night of May 15-16 he returned to Cyprus, and about 3,000 defenders of the city joined his detachment.

The remaining garrison numbered 12–13,000 men. They fought off enemy attacks until May 18, when the Muslims were able to smash the gates, dismantle the gaps in the walls filled up by the defenders and burst into the streets of Accra. The Egyptians killed Christian men and took women and children captive. Some of the defenders were able to make their way to the harbor, where they boarded ships and went to Cyprus. But a storm arose at sea, and many ships sank.

Several thousand of the crusaders who remained on the shore took refuge in the Templar castle, which the Sultan’s troops were quickly able to capture by storm. Some of the Christian warriors were able to break through to the sea and board ships, the rest were exterminated by the Egyptians. Accra was burned and razed to the ground. This was retaliation for the murder of the Egyptian garrison of Accra, which was committed by the King of England, Richard the Lionheart. After the fall of Accra, Christians abandoned several small towns in Syria that were under their control. This was the inglorious end of the Crusades.

CRUSADES

(1095-1291), a series of military campaigns in the Middle East undertaken by Western European Christians in order to liberate the Holy Land from Muslims. The Crusades were the most important stage in the history of the Middle Ages. All social strata of Western European society were involved in them: kings and commoners, the highest feudal nobility and clergy, knights and servants. People who took the crusader vow had different motives: some sought to get rich, others were attracted by a thirst for adventure, and others were driven solely by religious feelings. The Crusaders sewed red breast crosses onto their clothes; when returning from a campaign, the signs of the cross were sewn onto the back. Thanks to legends, the Crusades were surrounded by an aura of romance and grandeur, knightly spirit and courage. However, stories about gallant crusader knights are replete with exaggerations beyond measure. In addition, they overlook the “insignificant” historical fact that, despite the valor and heroism shown by the crusaders, as well as the appeals and promises of the popes and confidence in the rightness of their cause, Christians were never able to liberate the Holy Land. The Crusades only resulted in Muslims becoming the undisputed rulers of Palestine.

Causes of the Crusades. The crusades began with the popes, who were nominally considered the leaders of all enterprises of this kind. The popes and other instigators of the movement promised heavenly and earthly rewards to all those who would put their lives in danger for the holy cause. The campaign to recruit volunteers was particularly successful due to the religious fervor that reigned in Europe at the time. Whatever their personal motives for participating (and in many cases they played a vital role), the soldiers of Christ were confident that they were fighting for a just cause.

Conquests of the Seljuk Turks. The immediate cause of the Crusades was the growth of the power of the Seljuk Turks and their conquest of the Middle East and Asia Minor in the 1070s. Coming from Central Asia, at the beginning of the century the Seljuks penetrated into Arab-controlled areas, where they were initially used as mercenaries. Gradually, however, they became more and more independent, conquering Iran in the 1040s, and Baghdad in 1055. Then the Seljuks began to expand the borders of their possessions to the west, leading an offensive mainly against the Byzantine Empire. The decisive defeat of the Byzantines at Manzikert in 1071 allowed the Seljuks to reach the shores of the Aegean Sea, conquer Syria and Palestine, and take Jerusalem in 1078 (other dates are also indicated). The threat from the Muslims forced the Byzantine emperor to turn to Western Christians for help. The fall of Jerusalem greatly disturbed the Christian world.

Religious motives. The conquests of the Seljuk Turks coincided with a general religious revival in Western Europe in the 10th and 11th centuries, which was largely initiated by the activities of the Benedictine monastery of Cluny in Burgundy, founded in 910 by the Duke of Aquitaine, William the Pious. Thanks to the efforts of a number of abbots who persistently called for the purification of the church and the spiritual transformation of the Christian world, the abbey became a very influential force in the spiritual life of Europe. At the same time in the 11th century. the number of pilgrimages to the Holy Land increased. The “infidel Turk” was portrayed as a desecrator of shrines, a pagan barbarian, whose presence in the Holy Land is intolerable for God and man. In addition, the Seljuks posed an immediate threat to the Christian Byzantine Empire.

Economic incentives. For many kings and barons, the Middle East seemed like a world of great opportunity. Lands, income, power and prestige - all this, they believed, would be the reward for the liberation of the Holy Land. Due to the expansion of the practice of inheritance based on primogeniture, many younger sons of feudal lords, especially in the north of France, could not count on participating in the division of their father's lands. By taking part in the crusade, they could hope to acquire the land and position in society that their older, more successful brothers enjoyed. The Crusades gave peasants the opportunity to free themselves from lifelong serfdom. As servants and cooks, peasants formed the convoy of the Crusaders. For purely economic reasons, European cities were interested in the crusades. For several centuries, the Italian cities of Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa and Venice battled Muslims for dominance over the western and central Mediterranean. By 1087, the Italians had driven the Muslims out of southern Italy and Sicily, founded settlements in North Africa, and took control of the western Mediterranean. They launched sea and land invasions of Muslim territories in North Africa, forcing trade privileges from local residents. For these Italian cities, the Crusades only meant a transfer of military operations from the western Mediterranean to the eastern.

THE BEGINNING OF THE CRUSADES

The beginning of the Crusades was proclaimed at the Council of Clermont in 1095 by Pope Urban II. He was one of the leaders of the Cluny reform and devoted many meetings of the council to discussing the troubles and vices that hindered the church and clergy. On November 26, when the council had already completed its work, Urban addressed a huge audience, probably numbering several thousand representatives of the highest nobility and clergy, and called for a war against infidel Muslims in order to liberate the Holy Land. In his speech, the pope emphasized the sanctity of Jerusalem and the Christian relics of Palestine, spoke of the plunder and desecration to which they were subjected by the Turks, and outlined the numerous attacks on pilgrims, and also mentioned the danger facing Christian brothers in Byzantium. Then Urban II called on his listeners to take up the holy cause, promising everyone who went on the campaign absolution, and everyone who laid down their lives in it - a place in paradise. The pope called on the barons to stop destructive civil strife and turn their ardor to a charitable cause. He made it clear that the crusade would provide the knights with ample opportunities to gain lands, wealth, power and glory - all at the expense of the Arabs and Turks, whom the Christian army would easily deal with. The response to the speech was the shouts of the listeners: “Deus vult!” (“God wants it!”). These words became the battle cry of the crusaders. Thousands of people immediately vowed that they would go to war.

The first crusaders. Pope Urban II ordered the clergy to spread his call throughout Western Europe. Archbishops and bishops (the most active among them was Adhemar de Puy, who took the spiritual and practical leadership of the preparations for the campaign) called on their parishioners to respond to it, and preachers like Peter the Hermit and Walter Golyak conveyed the pope’s words to the peasants. Often, preachers aroused such religious fervor in the peasants that neither their owners nor local priests could restrain them; they took off in thousands and set off on the road without supplies and equipment, without the slightest idea of the distance and hardships of the journey, in naive confidence, that God and the leaders will take care of both that they do not get lost and their daily bread. These hordes marched across the Balkans to Constantinople, expecting to be treated with hospitality by fellow Christians as champions of a holy cause. However, the local residents greeted them coolly or even with contempt, and then the Western peasants began to loot. In many places, real battles took place between the Byzantines and the hordes from the west. Those who managed to get to Constantinople were not at all welcome guests of the Byzantine Emperor Alexei and his subjects. The city temporarily settled them outside the city limits, fed them and hastily transported them across the Bosporus to Asia Minor, where the Turks soon dealt with them.

1st Crusade (1096-1099). The 1st Crusade itself began in 1096. Several feudal armies took part in it, each with its own commander-in-chief. They arrived in Constantinople by three main routes, by land and sea, during 1096 and 1097. The campaign was led by feudal barons, including Duke Godfrey of Bouillon, Count Raymond of Toulouse and Prince Bohemond of Tarentum. Formally, they and their armies obeyed the papal legate, but in fact they ignored his instructions and acted independently. The crusaders, moving overland, took food and fodder from the local population, besieged and plundered several Byzantine cities, and repeatedly clashed with Byzantine troops. The presence of a 30,000-strong army in and around the capital, demanding shelter and food, created difficulties for the emperor and the inhabitants of Constantinople. Fierce conflicts broke out between the townspeople and the crusaders; At the same time, disagreements between the emperor and the military leaders of the crusaders worsened. Relations between the emperor and the knights continued to deteriorate as the Christians moved east. The crusaders suspected that the Byzantine guides were deliberately luring them into ambushes. The army turned out to be completely unprepared for sudden attacks by enemy cavalry, which managed to hide before the knightly heavy cavalry rushed in pursuit. The lack of food and water aggravated the hardships of the campaign. Wells along the way were often poisoned by Muslims. Those who endured these most difficult trials were rewarded with their first victory when Antioch was besieged and taken in June 1098. Here, according to some evidence, one of the crusaders discovered a shrine - a spear with which a Roman soldier pierced the side of the crucified Christ. This discovery is reported to have greatly inspired the Christians and contributed greatly to their subsequent victories. The fierce war lasted another year, and on July 15, 1099, after a siege that lasted little more than a month, the Crusaders took Jerusalem and put its entire population, Muslims and Jews, to the sword.

Kingdom of Jerusalem. After much debate, Godfrey of Bouillon was elected king of Jerusalem, who, however, unlike his not so modest and less religious successors, chose the unassuming title of “Defender of the Holy Sepulcher.” Godfrey and his successors were given control of a power united only nominally. It consisted of four states: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli and the Kingdom of Jerusalem itself. The King of Jerusalem had rather conditional rights in relation to the other three, since their rulers had established themselves there even before him, so they fulfilled their vassal oath to the king (if they performed) only in the event of a military threat. Many sovereigns made friends with the Arabs and Byzantines, despite the fact that such a policy weakened the position of the kingdom as a whole. Moreover, the king's power was significantly limited by the church: since the Crusades were carried out under the auspices of the church and nominally led by the papal legate, the highest cleric in the Holy Land, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, was an extremely influential figure there.

Population. The kingdom's population was very diverse. In addition to the Jews, there were many other nations present here: Arabs, Turks, Syrians, Armenians, Greeks, etc. Most of the crusaders came from England, Germany, France and Italy. Since there were more French, the crusaders were collectively called Franks.

Coastal cities. At least ten important centers of commerce and trade developed during this time. Among them are Beirut, Acre, Sidon and Jaffa. In accordance with privileges or grants of powers, Italian merchants established their own administration in coastal cities. Usually they had their own consuls (heads of administration) and judges here, acquired their own coins and a system of weights and measures. Their legislative codes also applied to the local population. As a rule, the Italians paid taxes on behalf of the townspeople to the king of Jerusalem or his governors, but in their daily activities they enjoyed complete independence. Special quarters were allocated for the residences and warehouses of the Italians, and near the city they planted gardens and vegetable gardens in order to have fresh fruits and vegetables. Like many knights, Italian merchants made friends with Muslims, of course, in order to make a profit. Some even went so far as to include sayings from the Koran on coins.

Spiritual knightly orders. The backbone of the crusader army was formed by two orders of chivalry - the Knights Templar (Templars) and the Knights of St. John (Johnnites or Hospitallers). They included predominantly the lower strata of the feudal nobility and the younger scions of aristocratic families. Initially, these orders were created to protect temples, shrines, roads leading to them and pilgrims; provision was also made for the creation of hospitals and care for the sick and wounded. Since the orders of the Hospitallers and Templars set religious and charitable goals along with military ones, their members took monastic vows along with the military oath. The orders were able to replenish their ranks in Western Europe and receive financial assistance from those Christians who were unable to take part in the crusade, but were eager to help the holy cause. Due to such contributions, the Templars in the 12-13th centuries. essentially turned into a powerful banking house that provided financial intermediation between Jerusalem and Western Europe. They subsidized religious and commercial enterprises in the Holy Land and gave loans to the feudal nobility and merchants here in order to obtain them in Europe.

SUBSEQUENT CRUSADES

2nd Crusade (1147-1149). When Edessa was captured by the Muslim ruler of Mosul, Zengi, in 1144 and news of this reached Western Europe, the head of the Cistercian monastic order, Bernard of Clairvaux, convinced the German Emperor Conrad III (reigned 1138-1152) and King Louis VII of France (reigned 1137-1180) to undertake a new crusade. This time, Pope Eugene III issued a special bull on the Crusades in 1145, which contained precisely formulated provisions that guaranteed the families of the crusaders and their property the protection of the church. The forces that were able to attract participation in the campaign were enormous, but due to the lack of cooperation and a well-thought-out campaign plan, the campaign ended in complete failure. Moreover, he gave the Sicilian king Roger II a reason to raid Byzantine possessions in Greece and the islands of the Aegean Sea.

3rd Crusade (1187-1192). If Christian military leaders were constantly in discord, then Muslims under the leadership of Sultan Salah ad-din united into a state that stretched from Baghdad to Egypt. Salah ad-din easily defeated the divided Christians, took Jerusalem in 1187 and established control over the entire Holy Land, with the exception of a few coastal cities. The 3rd Crusade was led by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (reigned 1152-1190), the French king Philip II Augustus (reigned 1180-1223) and the English king Richard I the Lionheart (reigned 1189-1199). The German emperor drowned in Asia Minor while crossing a river, and only a few of his warriors reached the Holy Land. Two other monarchs who competed in Europe took their disputes to the Holy Land. Philip II Augustus, under the pretext of illness, returned to Europe to try, in the absence of Richard I, to take away the Duchy of Normandy from him. Richard the Lionheart remained the only leader of the crusade. The exploits he accomplished here gave rise to legends that surrounded his name with an aura of glory. Richard recaptured Acre and Jaffa from the Muslims and concluded an agreement with Salah ad-din on unimpeded access for pilgrims to Jerusalem and some other shrines, but he failed to achieve more. Jerusalem and the former Kingdom of Jerusalem remained under Muslim rule. Richard's most significant and lasting achievement in this campaign was his conquest of Cyprus in 1191, where as a result the independent Kingdom of Cyprus arose, which lasted until 1489.

4th Crusade (1202-1204). The 4th Crusade, announced by Pope Innocent III, was mainly carried out by the French and Venetians. The vicissitudes of this campaign are described in the book of the French military leader and historian Geoffroy Villehardouin, The Conquest of Constantinople - the first lengthy chronicle in French literature. According to the initial agreement, the Venetians undertook to deliver the French crusaders by sea to the shores of the Holy Land and provide them with weapons and provisions. Of the expected 30 thousand French soldiers, only 12 thousand arrived in Venice, who, due to their small numbers, could not pay for the chartered ships and equipment. Then the Venetians proposed to the French that, as payment, they would assist them in an attack on the port city of Zadar in Dalmatia, which was the main rival of Venice in the Adriatic, subject to the Hungarian king. The original plan - to use Egypt as a springboard for an attack on Palestine - was put on hold for the time being. Having learned about the plans of the Venetians, the pope forbade the expedition, but the expedition took place and cost its participants excommunication. In November 1202, a combined army of Venetians and French attacked Zadar and thoroughly plundered it. After this, the Venetians suggested that the French once again deviate from the route and turn against Constantinople in order to restore the deposed Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelus to the throne. A plausible pretext was also found: the crusaders could count on that, in gratitude, the emperor would give them money, people and equipment for an expedition to Egypt. Ignoring the pope's ban, the crusaders arrived at the walls of Constantinople and returned the throne to Isaac. However, the question of payment of the promised reward hung in the air, and after an uprising occurred in Constantinople and the emperor and his son were removed, hopes for compensation melted away. Then the crusaders captured Constantinople and plundered it for three days starting on April 13, 1204. The greatest cultural values were destroyed, and many Christian relics were plundered. In place of the Byzantine Empire, the Latin Empire was created, on the throne of which Count Baldwin IX of Flanders was placed. The empire that existed until 1261 of all the Byzantine lands included only Thrace and Greece, where the French knights received feudal appanages as a reward. The Venetians owned the harbor of Constantinople with the right to levy duties and achieved a trade monopoly within the Latin Empire and on the islands of the Aegean Sea. Thus, they benefited the most from the crusade, but its participants never reached the Holy Land. The pope tried to extract his own benefits from the current situation - he lifted the excommunication from the crusaders and took the empire under his protection, hoping to strengthen the union of the Greek and Catholic churches, but this union turned out to be fragile, and the existence of the Latin Empire contributed to the deepening of the schism.

Children's Crusade (1212). Perhaps the most tragic of attempts to return the Holy Land. The religious movement, which originated in France and Germany, involved thousands of peasant children who were convinced that their innocence and faith would achieve what adults could not achieve by force of arms. The religious fervor of the teenagers was fueled by their parents and parish priests. The pope and the higher clergy opposed the enterprise, but were unable to stop it. Several thousand French children (possibly up to 30,000), led by the shepherd Etienne from Cloix near Vendôme (Christ appeared to him and handed him a letter to give to the king), arrived in Marseilles, where they were loaded onto ships. Two ships sank during a storm in the Mediterranean Sea, and the remaining five reached Egypt, where the shipowners sold the children into slavery. Thousands of German children (estimated at up to 20 thousand), led by ten-year-old Nicholas from Cologne, headed to Italy on foot. While crossing the Alps, two-thirds of the detachment died from hunger and cold, the rest reached Rome and Genoa. The authorities sent the children back, and on the way back almost all of them died. There is another version of these events. According to it, French children and adults, led by Etienne, first arrived in Paris and asked King Philip II Augustus to organize a crusade, but the king managed to persuade them to go home. The German children, under the leadership of Nicholas, reached Mainz, here some were persuaded to return, but the most stubborn continued their journey to Italy. Some arrived in Venice, others in Genoa, and a small group reached Rome, where Pope Innocent released them from their vow. Some children showed up in Marseille. Be that as it may, most of the children disappeared without a trace. Perhaps in connection with these events, the famous legend about the rat catcher from Hammeln arose in Germany. The latest historical research casts doubt on both the scale of this campaign and its very fact in the version as it is usually presented. It has been suggested that the “Children’s Crusade” actually refers to the movement of the poor (serfs, farm laborers, day laborers) who had already failed in Italy and gathered for a crusade.

5th Crusade (1217-1221). At the 4th Lateran Council in 1215, Pope Innocent III declared a new crusade (sometimes it is considered as a continuation of the 4th campaign, and then the subsequent numbering is shifted). The performance was scheduled for 1217, it was led by the nominal king of Jerusalem, John of Brienne, the king of Hungary, Andrew (Endre) II, and others. In Palestine, military operations were sluggish, but in 1218, when new reinforcements arrived from Europe, the crusaders shifted the direction of their attack to Egypt and captured the city of Damiettu, located on the seashore. The Egyptian Sultan offered the Christians to cede Jerusalem in exchange for Damietta, but the papal legate Pelagius, who was expecting the approach of the legendary Christian “King David” from the east, did not agree to this. In 1221, the crusaders launched an unsuccessful assault on Cairo, found themselves in a difficult situation and were forced to surrender Damietta in exchange for an unhindered retreat.

6th Crusade (1228-1229). This crusade, sometimes called "diplomatic", was led by Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, grandson of Frederick Barbarossa. The king managed to avoid hostilities; through negotiations, he (in exchange for a promise to support one of the parties in the inter-Muslim struggle) received Jerusalem and a strip of land from Jerusalem to Acre. In 1229 Frederick was crowned king in Jerusalem, but in 1244 the city was again conquered by the Muslims.

7th Crusade (1248-1250). It was headed by the French king Louis IX the Saint. The military expedition undertaken against Egypt turned into a crushing defeat. The crusaders took Damietta, but on the way to Cairo they were completely defeated, and Louis himself was captured and forced to pay a huge ransom for his release.

8th Crusade (1270). Not heeding the warnings of his advisers, Louis IX again went to war against the Arabs. This time he targeted Tunisia in North Africa. The crusaders found themselves in Africa during the hottest time of the year and survived a plague epidemic that killed the king himself (1270). With his death, this campaign ended, which became the last attempt of Christians to liberate the Holy Land. Christian military expeditions to the Middle East ceased after the Muslims took Acre in 1291. However, in the Middle Ages, the concept of "crusade" was applied to various kinds of religious wars of Catholics against those whom they considered enemies of the true faith or the church that embodied this faith, in including the Reconquista - the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslims that lasted seven centuries.

RESULTS OF THE CRUSADES

Although the Crusades did not achieve their goal and, begun with general enthusiasm, ended in disaster and disappointment, they constituted an entire era in European history and had a serious impact on many aspects of European life.

Byzantine Empire. The Crusades may have indeed delayed the Turkish conquest of Byzantium, but they could not prevent the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The Byzantine Empire was in a state of decline for a long time. Its final death meant the emergence of the Turks on the European political scene. The sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 and the Venetian trade monopoly dealt the empire a mortal blow, from which it could not recover even after its revival in 1261.

Trade. The biggest beneficiaries of the Crusades were the merchants and artisans of the Italian cities, who provided the crusader armies with equipment, provisions and transport. In addition, Italian cities, especially Genoa, Pisa and Venice, were enriched by a trade monopoly in the Mediterranean countries. Italian merchants established trade relations with the Middle East, from where they exported various luxury goods to Western Europe - silks, spices, pearls, etc. The demand for these goods brought super profits and stimulated the search for new, shorter and safer routes to the East. Ultimately, this search led to the discovery of America. The Crusades also played an extremely important role in the emergence of the financial aristocracy and contributed to the development of capitalist relations in Italian cities.

Feudalism and the Church. Thousands of large feudal lords died in the Crusades, in addition, many noble families went bankrupt under the burden of debt. All these losses ultimately contributed to the centralization of power in Western European countries and the weakening of the system of feudal relations. The impact of the Crusades on the authority of the church was controversial. If the first campaigns helped strengthen the authority of the Pope, who took on the role of spiritual leader in the holy war against Muslims, then the 4th Crusade discredited the power of the Pope even in the person of such an outstanding representative as Innocent III. Business interests often took precedence over religious considerations, forcing the crusaders to disregard papal prohibitions and enter into business and even friendly contacts with Muslims.

Culture. It was once generally accepted that it was the Crusades that brought Europe to the Renaissance, but now such an assessment seems overestimated to most historians. What they undoubtedly gave the man of the Middle Ages was a broader view of the world and a better understanding of its diversity. The Crusades were widely reflected in literature. A countless number of poetic works were composed about the exploits of the crusaders in the Middle Ages, mostly in Old French. Among them there are truly great works, such as the History of the Holy War (Estoire de la guerre sainte), describing the exploits of Richard the Lionheart, or the Song of Antioch (Le chanson d'Antioche), supposedly composed in Syria, dedicated to the 1st Crusade . New artistic material born of the Crusades also penetrated into ancient legends. Thus, the early medieval cycles about Charlemagne and King Arthur were continued. The Crusades also stimulated the development of historiography. The conquest of Constantinople by Villehardouin remains the most authoritative source for the study of the 4th Crusade. The best medieval work in the genre of biography is considered by many to be the biography of King Louis IX, created by Jean de Joinville.One of the most significant medieval chronicles was the book written in Latin by Archbishop William of Tyre, History of Deeds in Overseas Lands (Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum), lively and reliable recreating the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1144 to 1184 (the year of the author's death).

LITERATURE

The era of the Crusades. M., 1914 Zaborov M. Crusades. M., 1956 Zaborov M. Introduction to the historiography of the Crusades (Latin chronography of the 11th-13th centuries). M., 1966 Zaborov M. Historiography of the Crusades (XV-XIX centuries). M., 1971 Zaborov M. History of the Crusades in documents and materials. M., 1977 Zaborov M. With a cross and a sword. M., 1979 Zaborov M. Crusaders in the East. M., 1980

Collier's Encyclopedia. - Open Society. 2000 .

| Source: | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Crusades, military expeditions of European Catholic militias to the east in 1096–1291, proclaiming as their goal the liberation of Christian holy sites in Palestine from Muslim rule.

Brutal persecution and massacres during the Crusades devastated the flourishing Jewish communities of the Rhine cities. These events are known in Jewish history as gzerot tatnav, that is, the massacre of 4856 according to the Jewish calendar (1096 - the beginning of the 1st Crusade). Some Jews were forced to be baptized, many chose martyrdom - Kiddush Hashem.

First Crusade

The desire to reconquer the Holy Land from Muslims appeared in Western Christianity at the beginning of the 11th century. as a result of religious ferment caused by the seizure of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher by the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim (1012).

According to some historians, this fermentation should also be attributed to the intensification from the 11th century. persecution of Jews - “god killers”.

The reason for the campaigns was the capture by the Seljuks in the last third of the 11th century. many Byzantine possessions in Asia Minor, as well as messages from Jerusalem, which they conquered from the Fatimids in 1071, about the oppression of Christian pilgrims by Muslims and about the “atrocities of the Jews” against Christians.

Calls of Pope Urban II and monk Peter of Amiens at the church council in Clermont (November 27, 1095) for a campaign against Muslims did not call for violence against Jews. But the traditional Christian view of the Jews as the culprits of the crucifixion of Jesus, as well as socio-economic reasons, (Jewish usury) at the very beginning of the 1st Crusade (1096–99) made Jews the target of attacks by the Crusaders.

In 1096, when crowds of knights, townspeople and peasants set out on the 1st Crusade. A wave of pogroms swept across Europe, the instigators of which declared that, setting out on a long campaign to liberate the Holy Sepulcher from the Christ-killing Gentiles, they could not tolerate their presence in their own land.

Crusader outrages in Western Europe

Murder of Jews in Metz (France) during the First Crusade.

In the First Crusade, the army of the poor, as the most inspired, set off first, and, having killed many Jews along the way, it gradually disintegrated and ceased to exist... Jacques le Goff, "The Civilization of the Medieval West", p. 70

The first detachments of crusaders, gathered in Rouen (France, 1096), almost completely exterminated the Jewish community, leaving only a few alive who agreed to be baptized. Frightened by this, as well as by the oath of one of the main leaders of the campaign, Duke Godfrey of Bouillon, to take revenge on the Jews for the blood of Jesus, the communities of France warned of the danger to the Jews of the Rhine communities of Germany.

Despite this, the Rhine communities only at the very last moment approached the emperor with a request for the protection promised in the privileges. Emperor Henry IV, who was informed by the head of the Jewish community of Mainz, Kalonimos ben Meshulam ha-Parnas, of the threats of Godfrey of Bouillon, ordered all dukes and bishops to protect the Jews from the crusaders. In the spring of 1096, pogroms spread to the Rhine region.

Godfrey of Bouillon, under pressure from the emperor, was forced to renounce his oath and, having arrived in Germany, even promised protection to the communities of Cologne and Mainz, who “gave” him 500 silver marks. Peter of Amiens, having entered Trier with his detachment (April 1096), did not conduct anti-Jewish agitation and limited himself to collecting food from the Jewish community for the crusaders. They paid huge sums to bishops and city garrison commanders to be provided with forts and auxiliaries for defense.

But the soldiers sent to protect the Jews refused to protect the Gentiles from the Christian soldiers going on the crusade, and abandoned the Jews to their fate. Some bishops, such as Cologne, sought to prevent pogroms by cruelly punishing the pogrom-makers - the death penalty or cutting off the hands; others, fearing for their lives, fled before the arrival of the crusaders, such as the Bishop of Mainz.

When waves of crusaders, mostly peasants and urban rabble, poured into the Rhineland from France, Lorraine and Germany, civil and ecclesiastical authorities failed to restrain them from committing excesses. The aristocracy that led the campaign did not, for the most part, participate in the violence against the Jews, but sought to avoid conflicts between participants over the Jews.

The least disciplined and more prone to violence, the common people subjected the communities of the Rhine region to severe defeat in May-July 1096. Particularly cruel were the detachments led by Count Emicho von Leiningen in Germany and Knight Volkmar in France. In Metz, 23 Jews were killed, the rest were baptized.

The defenselessness of the victims led to a previously unprecedented wave of violence, murders and robberies. There were cases when terrified Jews, and sometimes entire communities, converted to Christianity. But, as has happened before throughout Jewish history, most Jews were willing to die in the name of their faith. In many communities, for example, in Mainz, Xanten and others, Jews fought with all their strength, and when there was not the slightest hope of salvation, they took the lives of themselves and their families. Thousands of Jews accomplished this martyrdom.

Continuing their journey, the crusaders did not stop committing atrocities against the Jews.

Consequences of the First Crusade in the German Empire

Extermination of Jews in the Land of Israel

Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders in 1099. 13th century miniature, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

South wall of the Temple Mount. Templar fortress. Photo by Mikhail Margilov.

Entering Palestine from the north, the crusaders besieged Jerusalem on June 7, 1099 and captured it on July 15. The majority of the combat-ready Jewish population of Jerusalem, together with the Muslims, tried to resist the troops of Godfrey of Bouillon, and after the fall of the city Jews who took refuge in synagogues were burned. The rest were slaughtered or sold into slavery.

Large Jewish communities in the cities of Ramla and Jaffa were also destroyed.

Jewish settlements in Galilee remained unaffected. In the captured territories, the crusaders formed the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which stretched approximately from the area of modern Jubeil in Lebanon to Eilat (territorially finally formed at the beginning of the 12th century).

When the Crusaders opened transport routes from Europe, pilgrimages to the Holy Land became popular. At the same time, an increasing number of Jews sought to return to their homeland. Documents from the period show that 300 rabbis from France and England arrived in a group, with some settling in Accra (Acre), others in Jerusalem.

Second Crusade

The reason for the 2nd Crusade (1147–49) was the capture in 1144 by the Seljuks of Edessa (now Urfa, Turkey), which since 1098 had been the center of the Edessa County of the Crusaders.

Pope Eugene III's bull calling for a campaign exempted the participants of the campaign from paying interest on debts to creditors (mostly Jews), and the rulers of various countries completely freed the crusaders from paying debts to the Jews. More strict this time control of secular and ecclesiastical authorities over the masses of the crusaders to a large extent limited violence against Jews.

Unrest in Western Europe

In France, the decisive actions of King Louis VII (who led the campaign together with the German King Conrad III) and the sermons of church authority Bernard of Clairvaux protected the majority of the country's Jewish communities from the atrocities of the Crusaders. The exceptions were the communities of Rameru (in Champagne) and Carentan, in which the Jews, having fortified themselves in one of the courtyards, gave an unequal battle to the crowds of pogromists and all died.

In Germany, Conrad III, who patronized the Jews, failed to prevent the pogrom agitation of the Cistercian monk Rudolf(in some sources Radulf or Raulf), who went around the country preaching that the campaign should begin with the baptism or extermination of the Jews.

Jews, paying huge sums of money to feudal rulers and bishops, were able to take refuge in their castles for some time. Conrad III provided the Jews with refuge in his hereditary lands (Nuremberg, etc.), the Bishop of Cologne gave them the fortress of Wolkenburg, in which Jews defended themselves from the crusaders with weapons in their hands.

Unable to reach the Jews who had taken refuge in the castles, bands of crusaders killed or forced to be baptized every Jew who left the shelter. Bands of crusaders rampaged on the roads. Several Jews were killed in the vicinity of Cologne and Speyer. The economic life of the country was upset.

Situation in the Land of Israel

In Palestine, the 2nd Crusade ended with the conquest of Ashkelon. However, Benjamin of Tudela and Ptahia of Regensburg(who visited the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1160 and 1180 respectively) found well-established Jewish communities in Ashkelon, Ramla, Caesarea, Tiberias and Acre. Yehuda Al-Harizi's notes speak of a thriving community in Jerusalem, which he visited in 1216. Apparently unaffected Samaritan communities existed during this period in Nablus, Ashkelon, and Caesarea.

Third Crusade

The 3rd Crusade (1189–92) was sparked by the conquest of Jerusalem in 1187 by Salah al-Din.

During it Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, who headed it, took decisive measures suspended all attempts at violence against Jews in Germany. Jews were hidden in castles, the murder of a Jew was punishable by death, and wounding by cutting off a hand. The bishops threatened the rioters with excommunication and a ban on participating in the crusades.

For their salvation, the Jews again paid large sums of money to the authorities.

In France, King Philip II Augustus' attempts to prevent violence against Jews were unsuccessful. In a number of cities in central France, the crusaders organized the massacre of the Jewish population.

The greatest disasters befell the Jews of England, who were not harmed during the 1st and 2nd Crusades and even provided refuge in 1096 to French Jews fleeing the atrocities of the Crusaders. On September 3, 1189, the crusaders, who had gathered in London for the coronation ceremony of King Richard I the Lionheart, carried out a pogrom in the capital.

The king's attempt to stop the outrages failed: the dignitaries he sent to admonish the rioters were driven out by the crowd. Only three of the pogrom participants detained by the authorities were sentenced by the court, but not for violence against Jews, but for arson and robbery of the houses of Christians adjacent to the houses of Jews.

From London, the pogroms quickly spread to other cities in the country. Along with the mob, nobility and knighthood actively participated in the pogroms, who owed Jews large sums of money and wanted to get rid of debt payments. The Jewish communities of Lynn, Norwich, and Stamford were destroyed.

In Lincoln and some other cities, Jews escaped by taking refuge in royal castles. After the king went on campaign (beginning of 1190), the pogroms were repeated with greater force. The biggest pogrom took place in York. The Jewish community of Bury St Edmuns was hit hard, where 57 Jews were killed.

Late Crusades

In 1196, shortly before the preparation of the 4th Crusade (1201–1204), which apparently cost no Jewish victims, the crusaders killed 16 Jews in Vienna, for which two of the instigators of the pogrom were executed by Duke Frederick I.

The 5th–8th CRUSADES (1217–21; 1228–29; 1249–54; 1270) also took place without harmful consequences for the Jews of Europe.

The so-called children's crusade, who in 1212 set off from Germany and France to Provence and Italy. It cost the lives of several tens of thousands of children (some of them died during a storm on the Mediterranean Sea, some were sold into slavery).

Jerusalem, as a result of the 6th Crusade, was annexed to the Land of Israel, which still remained under the rule of the Crusaders (1229), and was finally lost by them in 1244.

In 1309, the Jews of many cities of Brabant (Belgium) who refused to accept baptism were killed by gathered crusaders.

The Shepherds' Crusades

New disasters befell the Jews of France during the two so-called Shepherds Crusades, the participants of which were mainly the dregs of society.

In 1251, the “shepherds,” heading to the East with the goal of reconquering Jerusalem and freeing Saint Louis IX, who had been in captivity by the Egyptians since 1250, defeated the Jewish communities of Paris, Orleans, Tours and Bourget.

They subjected the communities of Gascony and Provence to even greater destruction during their 2nd campaign (1320). Forty thousand militia - mostly teenagers as young as 16 - crossed France from north to south, destroying about 130 Jewish communities.

Pope John XXII, trying to stop the outrages, excommunicated all participants in the campaign. King Philip V, fearing losses to his treasury, ordered local authorities to protect Jews from "shepherds". But they everywhere met with the support of the mob and the middle layer of townspeople, including royal officials.

In Albi (southern France) the city authorities tried to stop the crowd at the city gates, but when the “shepherds”, shouting that they had come to kill Jews, burst into the city, the population greeted them with enthusiasm and took part in the beating.

In Toulouse, the monks released the leaders of the “shepherds” arrested by the governor, and declared their salvation a matter of divine intervention - the reward of the Almighty for the godly extermination of the Jews. During the massacre that followed, only those who were baptized were saved from death.

About 500 Jews besieged at the castle of Verdun-sur-Garonne committed suicide. In the papal possession - the county of Venessen - most of the Jewish community was baptized. Attempts of these " new Christians"Returns to Judaism were suppressed by the Inquisition.

From France, gangs of “shepherds” invaded Spain, where King Jaime II of Aragon, outraged by their outrages, defeated and scattered their gangs.

Consequences of the Crusades

The Crusades radically changed the position of Jews in Christian Europe. The dispute between Judaism and Christianity has lost its theological character.

The massacres and violence that accompanied the Crusades, which surpassed in cruelty all the misfortunes that have ever befallen the Jews since the rise of Christianity, revealed the full force of hatred towards the Jews and their faith, all the powerlessness of the Jews, who were constantly under threat, all the futility of the not always selfless efforts of the popes and kings to protect them.

In the 12th century. the idea of a Jewish conspiracy against Christians was first expressed, and the blood libel became widespread. Increasing religious fanaticism, which saw Jews as irreconcilable enemies of the Christian faith, found expression in increased discrimination and humiliation of Jews, culminating in the legislation of the Fourth Lateran (Ecumenical) Council (1215).

The Crusades dealt a heavy blow to the economic situation of the Jews. From the 13th century they lost their role as the main intermediary in Europe's trade with the East, since the movement of Jewish merchants across Christian Europe, whose roads were dominated by gangs of crusaders, became almost impossible. Deprived of their livelihood, the Jews were forced to turn to usury on a large scale.

Hated by the Christian environment, the Jews of medieval Europe, withdrawn into their communities, found sources of religious consolation and national pride in the memory of hundreds of communities exterminated by the crusaders and the many thousands of victims killed or martyred.

Federal Agency for Education

State educational institution of higher professional education

"Nizhny Novgorod State Linguistic University named after Dobrolyubov"

Translation faculty

Culture and history of France

"Crusades"

Performed:

1st year full-time student

training gr. 115 FPJ

Baturina Yu.V.

Nizhny Novgorod

Introduction

1. Background and reason for the Crusades

1.1 Preconditions in the East

1.2 Background in the West

1.3 Reason for the Crusades. Clermont Cathedral 1095

2. The course and order of the Crusades to the East

2.1 First Crusade

3. Results and consequences of the Crusades

3.1 Fall of Crusader power in the East

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

The Crusades are a series of military campaigns by Western European knights directed against “infidels” - Muslims, pagans, Orthodox states and various heretical movements. The goal of the first crusades was the liberation of Palestine, primarily Jerusalem (with the Holy Sepulcher), from the Seljuk Turks, but later the crusades were also carried out for the sake of converting the pagans of the Baltic states to Christianity, suppressing heretical and anti-clerical movements in Europe (Cathars, Hussites, etc. ) or solving the political problems of the popes.

The name “crusaders” appeared because participants in the crusades sewed crosses onto their clothes. It was believed that the participants in the campaign would receive forgiveness of sins, so not only knights, but also ordinary residents and even children went on campaigns. The first to embrace the idea of liberating Jerusalem from Turkish oppression was Pope Gregory VII, who wished to personally lead the campaign. Up to 50,000 enthusiasts responded to his call, but the pope’s struggle with the German emperor left the idea hanging in the air. Gregory's successor, Pope Victor III, renewed his predecessor's call, promising absolution, but not wanting to personally participate in the campaign. Residents of Pisa, Genoa, and some other Italian cities, which suffered from Muslim sea raids, equipped a fleet that departed for the African coast. The expedition burned two cities in Tunisia, but this episode did not receive wide resonance.

The true inspirer of the mass crusade was the simple beggar hermit Peter of Amiens, nicknamed the Hermit, originally from Picardy. When visiting Golgotha and the Holy Sepulcher, the sight of all kinds of oppression of Palestinian brothers in faith aroused strong indignation in him. Having received letters from the patriarch with a plea for help, Peter went to Rome to Pope Urban II, and then, wearing rags, without shoes, with his head uncovered and a crucifix in his hands, he went through the cities and villages of Europe, preaching wherever possible about the campaign for the liberation of Christians. and the Holy Sepulcher. Ordinary people, touched by his eloquence, took Peter for a saint and considered it happiness to even pinch off a piece of wool from his donkey as a souvenir. Thus the idea spread very widely and became popular.

The First Crusade began shortly after the passionate sermon of Pope Urban II at a church council in the French city of Clermont in November 1095. Shortly before this, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos turned to Urban with a request to help repel the attack of the warlike Seljuk Turks (named after their leader Seljuk). Perceiving the invasion of Muslim Turks as a threat to Christianity, the Pope agreed to help the emperor, and also, wanting to win public opinion on his side in the fight against another contender for the papal throne, he set an additional goal - to conquer the Holy Land from the Seljuks. The pope’s speech was repeatedly interrupted by outbursts of popular enthusiasm and cries of “It’s God’s will!” That’s what God wants!” Urban II promised the participants the cancellation of their debts and care for the families remaining in Europe. Right there, in Clermont, those wishing to take solemn oaths and, as a sign of the vow, sewed crosses made of strips of red fabric onto their clothes. This is where the name “crusaders” came from, and the name of their mission - “Crusade”.

The first campaign, on the wave of general enthusiasm, generally achieved its goals. Subsequently, Jerusalem and the Holy Land were recaptured by Muslims and the Crusades were undertaken to liberate them. The last (ninth) Crusade in its original meaning took place in 1271-1272. The last campaigns, also called “crusades,” were undertaken in the 15th century and were directed against the Hussites and Ottoman Turks.

Chapter 1. Prerequisites and reason for the Crusades

1.4 Prerequisites in the East

Christianity initially combined peaceful premises: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you and pray for those who abuse you. Give the other one to the one who hits you on the cheek, and do not prevent the one who takes your outer clothing from taking your shirt. Give to everyone who asks you, and do not demand back from the one who took what you have.”

In the 4th century, St. Basil the Great, with his 13th rule, proposed excommunicating from Communion for three years soldiers who killed in war, and his 55th rule excommunicated from Communion those who resisted the robbers by force of the sword. And even in the 10th century, Patriarch Polyeuctus of Constantinople excommunicated soldiers who defended their Orthodox fatherland from the invasion of Muslims (Turks) for 5 years.

The Crusades against Muslims continued for two centuries, until the very end of the 13th century. Both Christianity and Islam alike saw themselves as called to dominate the world. The rapid successes of Islam in the first century of its existence threatened European Christianity with serious danger: the Arabs conquered Syria, Palestine, Egypt, northern Africa, and Spain. The beginning of the 8th century was a critical moment: in the East, the Arabs conquered Asia Minor and threatened Constantinople, and in the West they tried to penetrate the Pyrenees. The victories of Leo the Isaurian and Charles Martel stopped the Arab expansion, and the further spread of Islam was stopped by the political disintegration of the Muslim world that soon began. The caliphate was fragmented into parts that were at war with each other.

In the second half of the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire even received the opportunity to return some of what was lost earlier: Nikephoros Phocas conquered Crete, part of Syria, and Antioch from the Arabs. In the 11th century, the situation changed again in a way unfavorable for Christians. After the death of Vasily II (1025), the Byzantine throne was occupied by weak emperors, who were constantly changing. The weakness of the supreme power turned out to be all the more dangerous for Byzantium because it was at this time that the eastern empire began to face serious danger in both Europe and Asia. In Western Asia, the Seljuks made their offensive movement to the West. Led by Shakir Beg (died 1059) and Toghrul Beg (died 1063), they brought most of Iran and Mesopotamia under their rule. Shakir's son Alp Arslan devastated Armenia, then a significant part of Asia Minor (1067-1070) and captured Emperor Roman Diogenes at Manzikert (1071). Between 1070 and 1081, the Seljuks took Syria and Palestine from the Egyptian Fatimids (Jerusalem in 1071-1073, Damascus in 1076), and Suleiman, the son of Kutulmish, a cousin of Togrul Beg, took all of Asia Minor from the Byzantines by 1081; Nicaea became his capital. Finally, the Turks took Antioch (1085). Again, as in the 8th century, the enemies were near Constantinople. At the same time, the European provinces of the empire were subjected (since 1048) to continuous invasions of the Pechenegs and Uzes, who sometimes caused terrible devastation right under the very walls of the capital. The year 1091 was especially difficult for the empire: the Turks, led by Chakha, were preparing an attack on Constantinople from the sea, and the Pecheneg army stood on land near the capital itself. Emperor Alexei Komnenos could not hope for success, fighting with his own troops alone: his forces had been largely exhausted in recent years in the war with the Italian Normans, who were trying to establish themselves on the Balkan Peninsula.

1.5 Prerequisites in the West

In the West, by the end of the 11th century, a number of reasons created a mood and situation favorable for the call to fight against the infidels, with which Emperor Alexius I Komnenos addressed there: religious feeling intensified extremely and an ascetic mood developed, which found expression in all kinds of spiritual exploits, between other things and on numerous pilgrimages.

In addition, in 1054 there was a Schism of the Christian Church (1054) - Catholics and Orthodox Christians anathematized each other.

Especially many pilgrims have long been heading to Palestine, to the Holy Sepulcher; in 1064, for example, Archbishop Siegfried of Mainz went to Palestine with a crowd of seven thousand pilgrims. The Arabs did not interfere with such pilgrimages, but Christian feelings were sometimes greatly offended by manifestations of Muslim fanaticism: for example, the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in 1009. Even then, under the impression of this event, Pope Sergius IV preached a holy war, but to no avail (after the death of Al-Hakim, however, the destroyed temples were restored). The establishment of the Turks in Palestine made Christian pilgrimages much more difficult, expensive and dangerous: pilgrims were much more likely to become victims of Muslim fanaticism. The stories of the returning pilgrims developed in the religiously minded masses of Western Christianity a feeling of grief over the sad fate of the holy places and strong indignation against the infidels. In addition to religious inspiration, there were other motives that powerfully acted in the same direction. In the 11th century, the passion for movement, which seemed to be the last echoes of the great migration of peoples (the Normans, their movements), had not yet completely died out. The establishment of the feudal system created in the knightly class a significant contingent of people who could not find application for their strength in their homeland (for example, younger members of baronial families) and were ready to go where there was hope of finding something better. Difficult socio-economic conditions attracted many people from the lower strata of society to the Crusades. In some Western countries (for example, in France, which provided the largest contingent of crusaders) in the 11th century, the situation of the masses became even more unbearable due to a number of natural disasters: floods, crop failures, and widespread diseases. The rich trading cities of Italy were ready to support crusader enterprises in the hope of significant trade benefits from the establishment of Christians in the East.

1.6 Reason for the Crusades. Clermont Cathedral 1095

The papacy, which had just strengthened its moral authority throughout the West with ascetic reform and had assimilated the idea of a single kingdom of God on earth, could not help but respond to the call addressed to it from Constantinople, in the hope of becoming the head of the movement and, perhaps, gaining spiritual power in the East. Finally, Western Christians have long been incited against Muslims by fighting them in Spain, Italy and Sicily. For all of southern Europe, Muslims were a familiar, hereditary enemy. All this contributed to the success of the appeal of Emperor Alexius I Komnenos, who already around 1089 was in relations with Pope Urban II and was apparently ready to put an end to church discord in order to receive help from the Latin West. There was talk of a council in Constantinople for this purpose; Dad freed Alexei from the excommunication that had hitherto been imposed on him as if he were a schismatic. When the pope was in Campania in 1091, Alexei's ambassadors were with him. In March 1095, the pope once again listened to Alexei's ambassadors (at the council in Piacenza), and in the fall of the same year a council was convened in Clermont (in France, in Auvergne). In the mind of Pope Urban II, the idea of helping Byzantium took on a form that would especially appeal to the masses. In the speech he delivered in Clermont, the political element was relegated to the background before the religious element: Urban II preached a campaign to liberate the Holy Land and the Holy Sepulcher from the infidels. The pope's speech in Clermont on November 24, 1095 was a huge success: many immediately vowed to go against the infidels and sewed crosses on their shoulders, which is why they were called “crusaders”, and the Campaigns were called “crusaders”. This gave impetus to a movement that was destined to stop only two centuries later. While the idea of a Crusade was ripening in the West, Emperor Alexei freed himself from the danger that forced him to seek help in the West. In 1091, he destroyed the Pecheneg horde, with the help of the Polovtsian khans Tugorkan and Bonyak; Chakha's maritime enterprise also ended unsuccessfully (Chakha was soon killed by order of the Nicene Sultan). Finally, in 1094-1095, Alexei managed to free himself from the danger that threatened him from his recent allies - the Polovtsians. The immediate danger for Byzantium passed just at the time when masses of the first crusaders began to arrive from the West, whom Alexei now looked at with alarm. Western assistance was too broad; it could threaten Byzantium itself, due to the enmity between the Latin West and the Greek East. The preaching of the Crusade was an extraordinary success in the West. The church stood at the head of the movement: the pope appointed Bishop Puy Adhemar as his legate to the crusader army, who was one of the first to accept the cross in Clermont. Those who accepted the cross, like pilgrims, were accepted by the church under its protection. Creditors could not demand debts from them during their journey; those who seized their property were excommunicated from the church; all the crusaders who went to the Holy Land, prompted to do so by piety, and not by the desire to acquire honors or wealth, were absolved of their sins. Already in the winter from 1095 to 1096, large masses of poorly or almost completely unarmed crusaders from the poorest classes gathered. They were led by Peter the Hermit and Walter Golyak (or Gautier the Beggar). Some of this crowd reached Constantinople, but many died earlier. The Greeks transported the crusaders to Asia, where almost all of them were exterminated by the Seljuks. Somewhat later, the real First Crusade began.

Chapter 2. The course and order of the Crusades to the East